The Inner Workings of a Load Cell

The Inner Workings of a Load Cell: A Comprehensive Guide

A load cell, a crucial component in many industries, is designed to accurately measure force or weight. But what lies beneath its exterior? Let’s delve into the inner workings of a load cell, exploring the Wheatstone bridge, strain gauges, types of load cells, and signal conditioning.

The Wheatstone Bridge: The Heart of the Load Cell

At the core of most load cells is the Wheatstone bridge, a simple yet powerful electrical circuit. It consists of four resistors arranged in a diamond shape. One of these resistors is the strain gauge, a crucial component that responds to changes in force or weight.

When a load is applied to the load cell, it deforms the strain gauge. This deformation changes the electrical resistance of the strain gauge. As a result, the balance of the Wheatstone bridge is upset. This imbalance generates a small electrical signal that is proportional to the applied load.

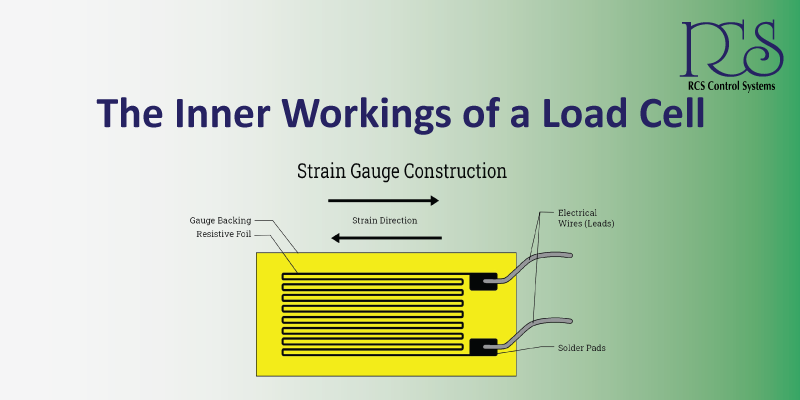

The Strain Gauge: The Sensor's Key

The strain gauge is a thin, metal foil or wire that is bonded to a flexible substrate. When the substrate is deformed, the strain gauge’s resistance changes. This change is due to the alteration in the length and cross-sectional area of the gauge.

Strain gauges can be made from various materials, including metals (like nickel-chromium alloy) and semiconductors. The choice of material affects the sensitivity and temperature coefficient of the gauge.

Types of Load Cells and Their Strain Gauge Configurations

Different types of load cells employ various strain gauge configurations to optimize their performance for specific applications. Here are a few common types:

1- Single-point load cells: These have a single strain gauge located at the point of maximum deflection. They are suitable for measuring vertical forces.

2- Shear beam load cells: These use a cantilever beam with strain gauges bonded to its sides. They are ideal for measuring both vertical and horizontal forces.

3- Compression load cells: These have strain gauges bonded to the top and bottom of a cylindrical or rectangular body. They are used for measuring compressive forces.

4- Torsion load cells: These have strain gauges bonded to a shaft that is subjected to torsional stress. They are used for measuring torque.

5- S-beam load cells: These use a beam with a cross-section resembling the letter “S.” They are highly sensitive and can measure both compressive and tensile forces.

6- Pancake load cells: These are low-profile load cells with strain gauges bonded to a circular diaphragm. They are often used in weighing systems where space is limited.

Signal Conditioning and Output

The electrical signal generated by the Wheatstone bridge is typically very small and requires amplification and conditioning before it can be used. This is achieved using electronic circuits within the load cell or in a separate signal conditioning unit.

Signal conditioning typically involves:

1- Amplification: Increasing the magnitude of the signal to a usable level.

2- Filtering: Removing noise and unwanted signals from the output.

3- Linearization: Compensating for non-linearity in the load cell’s response.

4- Temperature compensation: Correcting for changes in the load cell’s output due to temperature variations.

The output of a load cell can be analog (e.g., voltage or current) or digital (e.g., a digital signal transmitted via a communication protocol). The choice of output depends on the specific application and the requirements of the connected equipment.

Additional Considerations

Additional Considerations

- Accuracy: The accuracy of a load cell depends on factors such as the quality of the strain gauges, the design of the load cell, and the precision of the signal conditioning circuitry.

- Repeatability: A load cell should consistently produce the same output for a given input.

- Hysteresis: This is the difference between the load cell’s output when the load is increasing and decreasing. It should be minimized for accurate measurements.

- Overload protection: Load cells should be designed to withstand overload conditions without permanent damage.

- Environmental factors: Temperature, humidity, vibration, and electromagnetic interference can affect the performance of a load cell. Proper installation and shielding can help mitigate these effects.

In conclusion, load cells are sophisticated devices that rely on the Wheatstone bridge and strain gauges to accurately measure force or weight. By understanding the inner workings of these components, we can appreciate the precision and reliability of load cells in various industries, from manufacturing and transportation to scientific research and medical applications.